City of Beirut is an example of the way of building the city through history. The old city was destroyed and rebuilt several times throughout history.

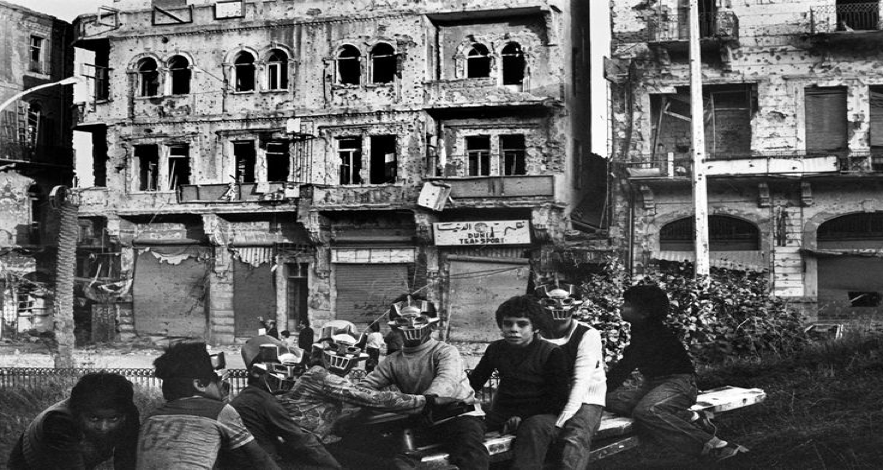

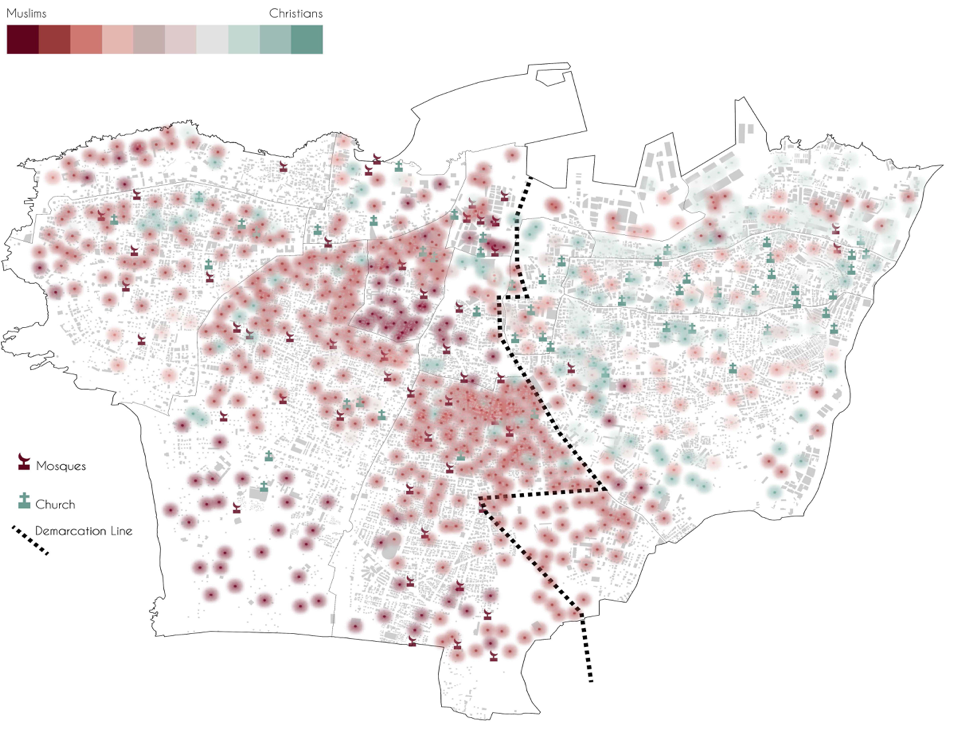

The establishment of the state of Israel after WW2 and the displacement of a hundred thousand Palestinian refugees to Lebanon (Palestinian refugees constituted 35% of the population between 1976-90) during the 1948 and 1967 exoduses contributed to shifting the demographic balance of the Muslim population and as a consequence religious conflicts increased. The Lebanese civil war from 1975 to 1990 not only caused the vast destruction of buildings and infrastructure, but also resulted in a large number of civilian victims. In addition, more than one third of the population became refugees in their own country. With the end of the hostilities in 1991, the once-pulsating country was split up into numerous enclaves, and society was deeply fragmented along religious lines.

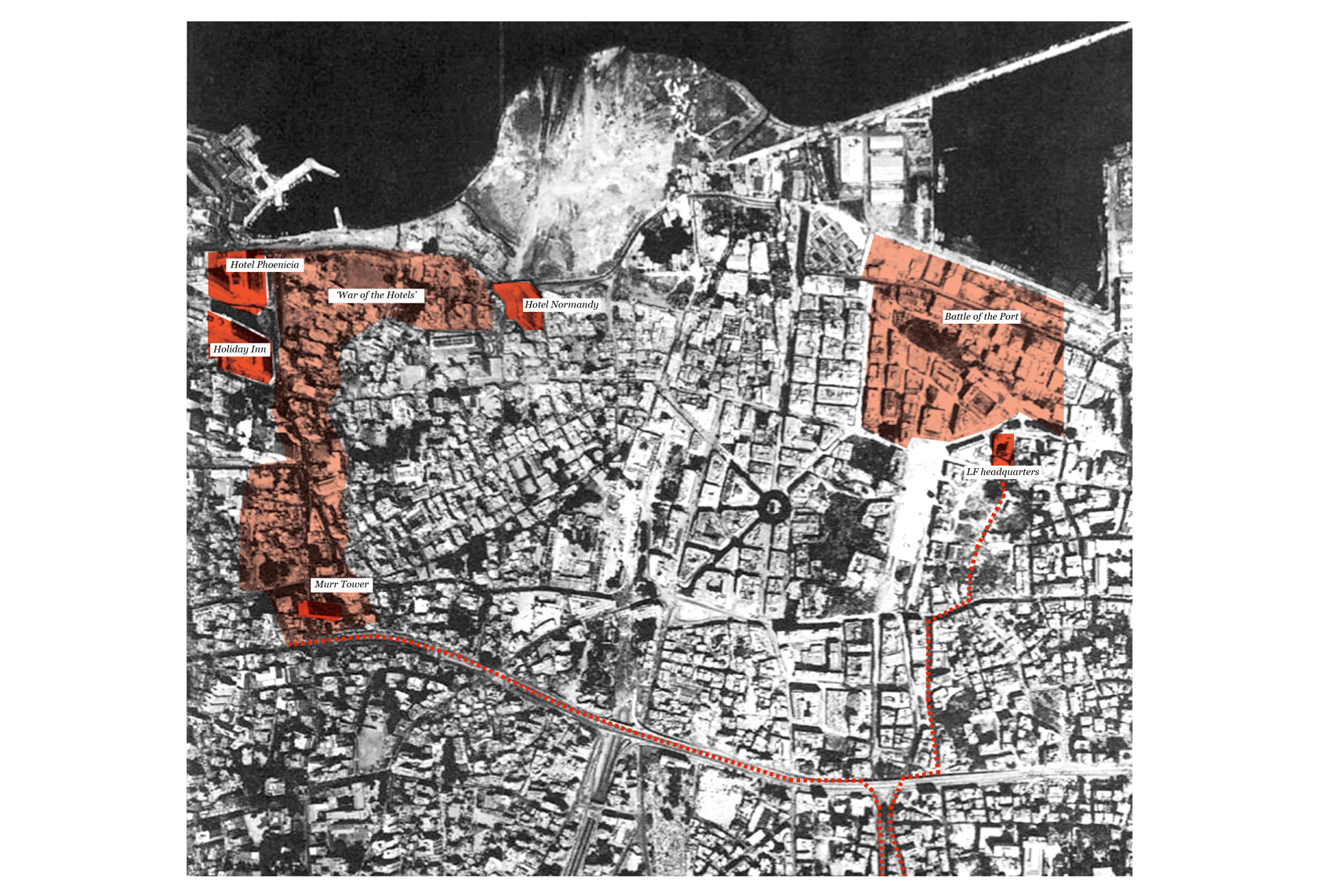

From 1975-1976, battles occurred between the PLO and the Phalanges, turning the heart of Beirut, which held both parties’ headquarters into a battlefield. Quickly the centre of the capital became a war zone, divided between both groups and the corresponding communities redistributed away from the centre, in the two sides, splitting the country in two, and causing waves of migrations across. By the end of the 16 year war, 25% of the population had been

displaced, and another 20-30% had permanently fled the country, leaving a very different communal distribution in the country. Beirut’s center was envisioned as a “melting pot”, where diverse sects and ideologies could interact peacefully and where Lebanon’s eighteen ethno-religious groups could intermingle freely. Sixteen year Lebanese civil war drastically transformed the physical landscape of the city and destroyed much more of its downtown area. From its former elegance, Beirut’s center was reduced to a “ghost town”.

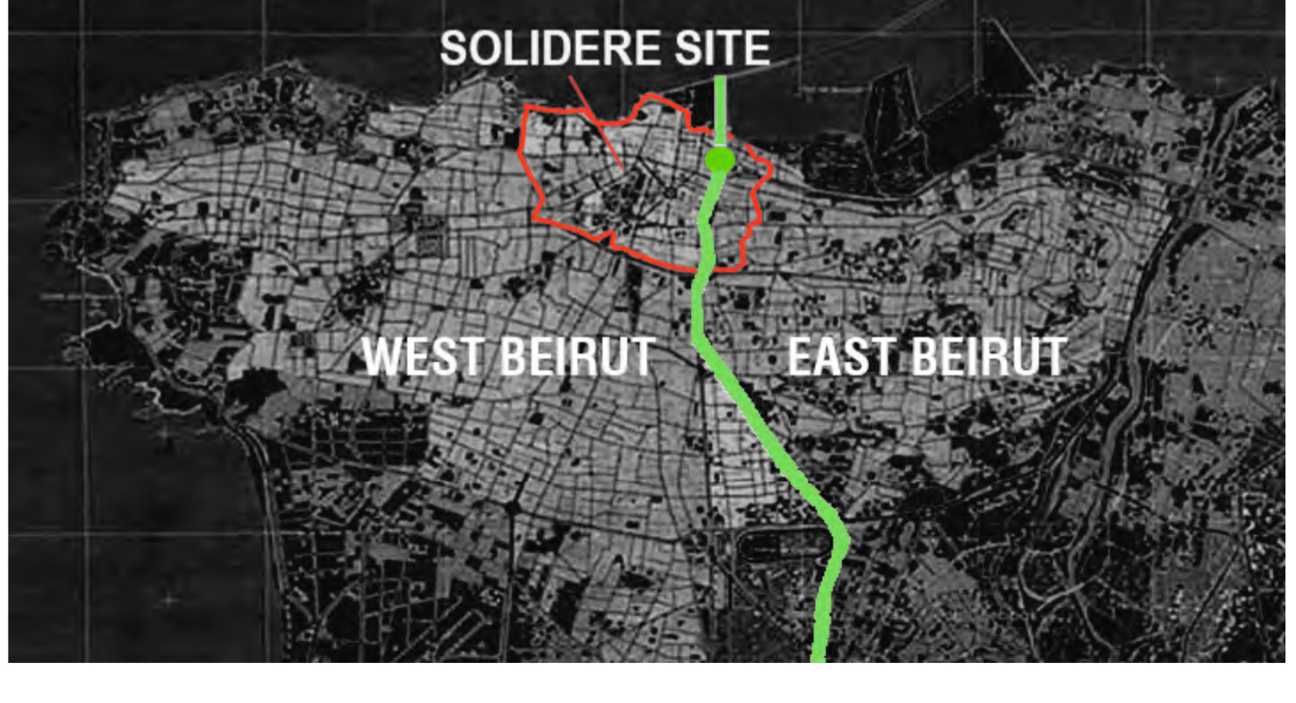

Beirut physical destruction was accompanied by a massive demographic upheaval, as fully half of its population was uprooted and relocated to temporary quarters in abandoned apartments, hotels and office buildings. In 1976, the ‘Green Line’, corresponds to the Old Damascus Road, divided the city into two as East and West Beirut. It became known as the ‘green line’ as the zone was essentially a no-man’s land during the cold periods of the civil war

and a confrontation line. The environment was thus often left to its own as no civilian could travel along the ‘green line’ in safe. Whilst most built forms where intensely devastated by the armed confrontations in around the ‘green line’, the natural environment expanded extensively during these fifteen years. Despite the construction of a number of parking lots along this dividing line today, the zone remains partially green. Its name pertains to trees and

bushes, not to peace as the colour green often refers to.

After the devastation brought by the civil war in Beirut, Building contractor Rafiq al-Hariri managed a privately organized solution and to carry out the reconstruction of Beirut through a private real estate company. The reconstruction strategy was primarily economic: the renewal of the whole of Lebanon would be based on the dynamism of tertiary functions in downtown Beirut, through the recreation of a regional hub oriented towards finance, business, culture and tourism. Main purposes are to make the country a holiday destination for wealthy people of the Middle East and to receive a share of Gulf capital.

This strategy was embodied in a vast urban project, entrusted in 1994 to a private land and real-estate and firm SOLIDERE, which adopted a planned approach of “insular urban development”. This approach led to the radical transformation of central Beirut, while the peri-central districts and the suburbs were barely, if at all, concerned by the project. For this purpose, Solidere released a huge number of development rights (4.7 million square metres of net floor space) covering an area twice the size of the pre- war city centre. About 80% of the buildings in the downtown area were quickly demolished—even if they could have been renovated. Stone buildings that delightfully blend Parisian and Ottoman styles have been lovingly restored. But the area feels antiseptic and fake, as though it had been built yesterday as an imitation of Beirut’s past. SOLIDERE’s design is prosthetic of core cultural elements divorced from Beirut and illustrative of privatist urbanism dominated by entrepreneurial ideals dichotomous to egalitarian notions to which good democratic governance should oblige. Moreover, the limits of the Solidere project for the reconstruction of central Beirut is called as the red line. Red line in Beirut also marked the tail of two cities. The Solidere site is designed and marketed towards an elitist clientele that is clearly contrastive to the middle-class and lower-middle class of Beirut. Dividing lines are the main features of divided cities. The “Green Line”, that separate Muslims and Christians of Beirut were shaped during Lebanese civil war, and the “Red Line” which separates the upper-class from the rest of the city.

After war, Solidere project, which aims to heal “heart of the city” to its former multicultural and vital characteristics, however; adds more lines to the city. Yet the project is not at heart an exercise in social and cultural reintegration. After implementation, different communities are physically and socio-economically separated.

The case of the reconstruction of the Beirut city, leads us to ask crucial questions about our Turkish case Diyarbakır, Suriçi; which are “How Turkish youth are negotiating Suriçi’s reconstruction?”, “How are the post-war generation imagining and spatially encountering their city?” and, “How does Suriçi’s rebuilt urban landscape, with its remnants of war, sites of displacement and transformed environs affect and inform identity, social interaction and perceptions of the past?”

References:

- Schmid, H. (2006). Privatized urbanity or a politicized society? Reconstruction in Beirut after the civil war. European Planning Studies, 14(3), 365-381.

- Kabbani, O. (1992). The reconstruction of Beirut. Oxford: Centre for Lebanese studies.

- Boano, C., Leclair-Paquet, B., & Wade, A. The Recovery of Beirut in the aftermath of the Lebanese Civil War: the Value of Urban Desig.

- Ghandour, M., & Fawaz, M. (2010). Spatial Erasure: Reconstruction Projects in Beirut. ArtEast Quarterly.

- Beirut: From City of Capital to Capital City. (n.d.). Retrieved November 29, 2016, from http://projectivecities.aaschool.ac.uk/portfolio/yasmina-el-chami-beirut-from-city-of- capital-to-capital-city/

- Nagel, C. (2002). Reconstructing space, re-creating memory: sectarian politics and urbandevelopment in post-war Beirut. Political Geography, 21(5), 717-725.

- Demirsoy, M. S. (2006). Kentsel Dönüşüm Projelerinin Kent Kimliği Üzerindeki Etkisi: Lübnan-Beyrut-Solidere Kentsel Dönüşüm Projesi Örnek Alan İncelemesi Mimar Sinan Güzel Sanatlar Üniversitesi. Fen Bilimleri Enstitüsü, Şehir ve Bölge Planlama Anabilim Dalı, Kentsel Tasarım Yüksek Lisans Tezi, İstanbul.

- Şisman, A., & Kibaroğlu, D. (2009). Dünyada Ve Türkiye’de Kentsel Dönüşüm Uygulamaları.

Authors: Berçem KAYA, Duygu KALKANLI